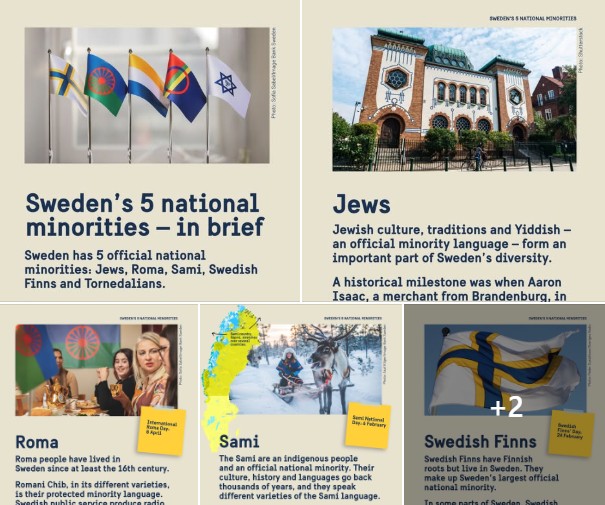

National minorities in Sweden

There are 5 official national minorities in Sweden. Swedish law protects their languages and cultures.

The national minorities in Sweden have long historical ties to the country. In 2000, Sweden recognised the following official minorities and minority languages: the Jews and Yiddish, the Roma and Romani Chib, the Sami and the Sami language, the Swedish Finns and Finnish, as well as the Tornedalians and Meänkieli (sometimes called Torne Valley Finnish).

This was in connection with Sweden’s ratification of the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

What is a national minority language?

To qualify as an official national minority language in Sweden, the language must meet two conditions: it must be a language, not a dialect, and people must have spoken it without interruption for at least three successive generations or 100 years.

In certain areas of Sweden, Sami, Swedish Finns and Tornedalians have historical roots and the minority groups still use their languages to a large extent. There, people have the right to use these languages to deal with administrative authorities. Sami, Swedish Finns and Tornedalians also have the right to use their languages in written contacs with certain national government agencies.

Children of the national minority groups in Sweden have the right to learn and use their minority language.

What does the law say about national minorities in Sweden?

The objective of Sweden’s National Minorities and Minority Languages Act (link in Swedish) from 2010 is to protect and promote the national minorities and their languages. What this means, in short:

Administrative authorities have an obligation to inform minorities about their rights. The public sector has a particular responsibility to protect and promote the minority languages and should support and promote the preservation and development of minorities’ cultural identities. Administrative authorities also have a duty to give minorities real influence on issues that affect them.

Jews

Jews started settling in Sweden at the end of the 17th century. In those days, Sweden demanded that Jews convert to Christianity, more specifically Lutheranism. In 1774, a Jewish man named Aaron Isaac came to Sweden from Germany. He became the first Jew that Sweden allowed to live in the country without converting. Isaac went on to found the first Jewish community in Stockholm. In 1870, Sweden granted Jews full civil rights.

During the 20th century, many Jews came to Sweden from Russia, Germany, Norway, Denmark, Hungary, former Czechoslovakia and Poland. In 1951, Sweden implemented freedom of religion, which meant that a Jewish person no longer needed to be a member of a Jewish community.

As for antisemitism in Sweden, a report from 2021 that compares 2020 with 2005, indicated that there had been a general decline in antisemitic attitudes and beliefs in Sweden. But antisemitism is still a cause for concern in the country, and in 2023, the Swedish government initiated a task force for Jewish life in Sweden, focused on safety and security. Jewish communities have also received more government support to improve the security around synagogues and other premises.

Roma

Roma people have lived in Sweden since at least the 16th century. For centuries, the Roma have been subjected to systematic discrimination and exclusion, partly due to policies of marginalisation.

Today, Sweden has action plans to combat antigypsyism, as well as other forms of racism. The Roma are a very heterogenerous group, living in many different countries and not associated with one particular faith. Many of the prejudice they face are based on negative images of Roma formed over centuries rather than the Roma people themselves.

In 2012, the Swedish government launched a long-term strategy that aims to achieve equal opportunities for Roma people by 2032. It covers the four key areas of education, employment, health and housing, as well as culture/language and civil society. The overall objective is that in 2032, a 20-year-old Roma person should have the same opportunities in life as a non-Roma person.

Sami

The Sami are not only an official minority, but also an indigenous people, who also live in Finland, Norway and Russia. Like many other indigenous people, the Sami have long been oppressed and their culture suppressed. In the 1950s, they began to influence Sweden’s policies by establishing associations to protect their rights. This developed until the Sami gained their own parliament, Sametinget, which holds special elections every four years.

The Sami parliament is both a parliament and a government agency. It works for greater autonomy and deals with matters related to hunting and fishing, reindeer herding, compensation for damage caused by predators, and Sami language and culture.

Today there are four major organisations that promote Sami national rights: the Sami Council (Samerådet), the two national federations Riksförbundet Same Ätnam (RSÄ, link in Swedish) and Svenska samernas Riksförbund (SSR, link in Swedish), and the youth organisation Sáminuorra.

Swedish Finns

Swedish Finns have Finnish roots but live in Sweden – a people with two cultures and two languages. And it’s up to individuals to define themselves as part of this minority.

The population mix has historical reasons. Following Sweden’s military campaigns in Finland in the 13th century, Finland gradually came under Swedish rule. Finland and Sweden only separated in 1809, with Sweden becoming a constitutional monarchy. The waves of Finnish immigration to Sweden did not stop with the separation of the two countries, because shortly thereafter Finland was occupied by Russia. Then, World War II led to the displacement of about 70,000 Finns to Sweden. The 1950s and 1960s also saw large numbers of Finns moving to Sweden, often for work.

Tornedalians

Ever since the Middle Ages, Finnish has been the dominant language in the Torne Valley, Tornedalen, the area around Torne River in the far north of Sweden. When Sweden and Finland separated in 1809, the countries drew the border along the river. In Western Torne Valley, which then became Swedish, Tornedalians lived. Their language, Meänkieli, is related to Finnish, Estonian and the Sami language, among others.

For a long time, Swedish minority policy didn’t allow Tornedalians to speak their own language in school – and the same applied to the Sami and Swedish Finns. The situation improved gradually from the 1960s onwards. Since 1 April 2000, Tornedalians have had the right to use their own language in all municipalities in the Torne Valley area.

The national minorities in Sweden – how many belong to each minority and where do they live?

Since Sweden doesn’t gather statistics on the basis of ethnicity or religion, there’s no official population count of each of these five minorities, only estimates. Sweden estimates its Jewish population at 20,000–25,000, the Roma 50,000–100,000, the Sami population 20,000–35,000. Swedish Finns are the largest national minority in Sweden, with a population of somewhere between 400,000 and 700,000 people, and the Tornedalians are around 50,000. According to these estimates, the five minorities constitute about 10 per cent of the total population of Sweden.

Most of the Sami minority live in the north and north-east of Sweden. It is the most widespread minority in terms of area. The Tornedalians mainly live in northern Sweden. The Swedish Finns live predominantly in the north-east, along the border with Finland, but also in central Sweden. The Roma and the Jews are spread over the country.